Residential land use growth

The restrained growth in residential land use in 2011 was mainly driven by demographics. The increase in the number of households slowed due to a reduced influx of immigrants to Germany over the past decade. This also occasioned a population decline in Germany since 2003. Moreover, falling birth rates in recent decades have resulted in a decrease in the numbers of young people and thus young families in Germany who are seeking family-friendly housing. And because fewer new housing units are needed, new housing construction has greatly declined, and with it land use for this purpose. Many German regions have experienced declines in both population and the numbers of households, resulting in higher vacancy rates and fewer housing starts.

Since 2011, the euro crisis combined with the free movement of workers has resulted in increased immigration to Germany. This has in turn triggered a population increase, albeit solely in regions with strong economic growth. New housing construction has also picked up somewhat, having bottomed out in 2009.

Commercial land use growth

The slowdown in land use growth is also attributable to economic factors. The slowdown in economic growth in many regions has translated into a slowdown in commercial land use growth. And in regions whose economies are still growing but where land prices tend to be high, there is a certain incentive to use land sparingly and to repurpose previously developed land.

However, no such incentive exists in economically weak regions where land prices are low. In fact the relatively few companies that are interested in opening a branch in such areas that will create new jobs are even in a position to require that new commercial property be developed for them at the target site. And this notwithstanding the fact that ample commercial property is available in both old and new industrial zones.

Land use for traffic infrastructures

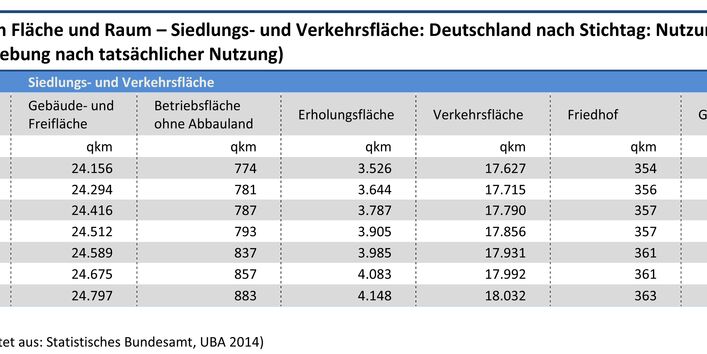

The rate of growth for traffic infrastructure elements has declined since 2000 by only 25 per cent, from 23 to 17 hectares per day.

This decline is solely attributable to a slowdown in the rate of new trunk road construction, from 10 to four hectares daily between 2000 and 2011, for the simple reason that less residential and commercial land use translates into a lesser need for new road construction.

All other types of traffic infrastructure land use, including other types of roads as well as railroad tracks, ports, airports, forestry roads and farming roads has continued unabated at a rate of 13 hectares daily.

Of this amount, seven hectares per day at a minimum were accounted for by expansion of the farming and forestry road network, which is for the most part financed by various farm subsidy or rural development programs.

Road construction for Germany’s national road network accounts for a maximum of 3.5 hectares daily, three hectares of which are used for highways, and 0.5 hectares of which are used for train tracks.

The remaining growth in traffic infrastructure land use is attributable to the construction of other main roads, as well as airports and ports.