Nowadays, allergies are among the most frequent chronic health problems in Germany. Roughly 15 % of adults have been diagnosed at least once in their life with hayfever (allergic rhinitis) whilst 9 % had a medical diagnosis of asthma bronchiale16. In the age group of children and juveniles 11 % have been diagnosed at least once in their life with hayfever whilst 6 % had a medical diagnosis of asthma17. Even higher than the number of people with this condition is the number of people who have been sensitised. In other words, once having made contact with the allergen, their body is more prone to respond with symptoms.

Allergenic types of pollen are the foremost trigger of hayfever. Notably, the occurrence of pollen is heavily dependent on the weather pattern or the climate. Higher temperatures, especially when combined with drought, and an extended vegetation period favour longer periods when pollen are air-borne as well as higher pollen concentrations. It is also conceivable that the allergenicity of pollen may increase as a function of temperature rise. Furthermore, there have been discussions on the possibility that an increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events might bring the phenomenon of ‘thunderstorm asthma’18 18 18 18 to the fore, thus giving it significance in clinical terms. A prerequisite for this would be a high concentration of pollen or spores in the air. Changes in the weather, such as precipitation, an increase in air humidity or lightning activity can lead to the fragmentation of pollen, thus producing smaller allergenic particles which can penetrate more deeply into the respiratory tract. Strong down-draughts transport these particles in direction of the ground, thus often leading to a sudden rise in the allergen concentration at breathing height. In people suffering from pollen allergies, this can cause severe symptoms.

In Germany, the pollen of hazel, alder, birch and ash trees as well as sweet grasses such as rye, mugwort and annual ragweed have particular relevance in terms of allergies. These are eight types of pollen to which the adult population of Germany is most frequently sensitised19. Apart from grass pollen, birch pollen is top of the ‘hit list’ as the cause of sensitisation. During the birch pollen season which – at the earliest – begins at the end of March, very high pollen concentrations can occur.

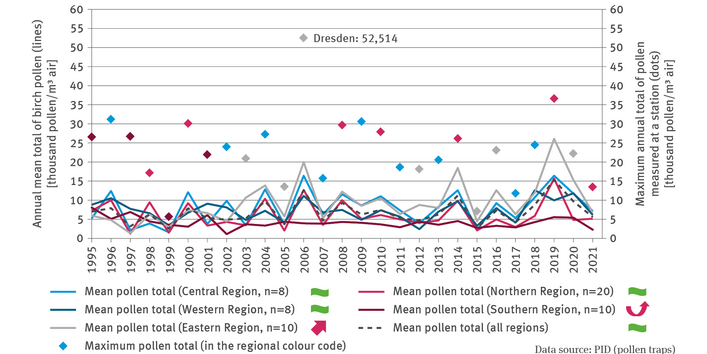

Scientific evidence has been found for close relationships between the occurrence of birch pollen burdens and climate change: Increased warmth and drought in spring lead to higher birch pollen counts. Pollen measurements conducted by the Foundation of German Pollen Information Service (PID), especially in 2019 and 2020 have demonstrated this. In 2019 the mean spring temperatures were distinctly higher by 1.3 °C and in 2020 by 2.5 °C than the long-term annual average in the period from 1961 to 1990. At the same time, precipitation – especially in the north-east of Germany – remained below average: lack of precipitation favours the distribution of pollen, thus remaining in the ambient air for a long time. In parts of Uckermark and Vorpommern less than 70 litres of rain fell locally per square meter in 2019. In spring 2020 precipitation reached only some 50 % of its multi-annual average. This was one of the six most precipitation-poor years since weather records began in 1881. Likewise, in 2020 the east of Germany recorded one of the highest precipitation deficits20 20.

The indicator is based on data from 56 pollen traps distributed throughout Germany within the PID measuring-network. Not all stations provide data in every year, as the regular operation of pollen traps cannot always be guaranteed. Occasionally there are locations which are abandoned after years of taking measurements, and then again others which are newly installed. Owing to these dynamics prevailing within the Messnetz, it is necessary to calculate for every year the mean across all available measuring stations.

As far as the whole of Germany is concerned, the time series has to date not indicated a statistically significant trend. It is important to realise that the developments have to be considered in a regionally differentiated manner. As to be expected, the birch pollen count is particularly high in those regions where birches are very widely distributed. The silver birch and also the weeping birch – the most important arboreal types of birch in Europe – are particularly widely distributed owing to their relatively low need of nutrients and water as well as their resilience to extreme weather conditions, with a distribution range from Scandinavia to southern Italy and from France as far as Russia. Nevertheless, the birch is primarily a boreal tree which, along with spruce, pine and aspen, can form climax forest communities in northerly regions. In southern Germany however, the silver birch is a pioneer tree species which, owing to the fact that it rapidly loses its growing strength, is therefore often eclipsed by other tree species in natural woodlands, thus sooner or later disappearing from forest stands. Nevertheless, it can happen that high pollen counts occur in connection with birch stands in some locations in the south and west of Germany. As a result, the maximum concentrations measured tend to alternate between stations and regions year by year. As shown by specific research on the development of the birch pollen season by means of pollen measurements in Munich, the days with particularly high concentrations (of more than 100 pollen per cubic metre) have become more frequent. This is important in clinical terms.21

In central, eastern and northern Germany, the concentration of birch pollen will at first increase with rising temperatures. In eastern Germany, the time series shows already now a significantly rising trend. However, according to model calculations for Bavaria, it is to be expected that in 40 years’ time, there will be distinctly less trouble from silver birch pollen affecting hayfever sufferers in the tree’s present main distribution region, as presumably by then, silver birches will find it too warm and too dry in that region. Their optimum temperature for photosynthesis is below 20 °C. By contrast, in regions at higher altitudes where temperatures will be milder then, the birch might extend its distribution range, thus leading to higher pollen counts.22

Moreover, the proliferation of birch trees will, in the near future, also be connected with increasing calamities in the forest. In areas where forest stands suffer wide-scale destruction owing to storm, heat or pathogens (cf. Indicator FW-I-5), pioneer tree species such as birch are able to take a hold, thus – at least temporarily – affecting the characteristics of a forest or woodland.

16 - Langen U., Schmitz R., Steppuhn H. 2013: Häufigkeit allergischer Erkrankungen in Deutschland: Ergebnisse der Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsbl 56 (5-6): 698–706. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1652-7.

17 - Thamm R., Poethko-Müller C., Hüther A., Thamm M. 2018: Allergische Erkrankungen bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland: Querschnittergebnisse aus KiGGS Welle 2 und Trends. Journal of Health Monitoring 3 (3): 3–18. doi: 10.17886/RKI-GBE-2018-075.

18 - Informationen der PID zum Gewitterasthma: https://www.pollenstiftung.de/pollenallergie/thunderstorm-asthma.html.

D’Amato G., Vitale C., D’Amato M., Cecchi L., Liccardi G., Molino A., Vatrella A., Sanduzzi A., Maesano C., Annesi-Maesano I. 2016: Thunderstorm-related asthma: what happens and why. Clin Exp Allergy 46(3): 390–6. doi: 10.1111/cea.12709.

D’Amato G., Holgate S.T., Pawankar R., Ledford D.K., Cecchi L., Al-Ahmad M. et al. 2015: Meteorological conditions, climate change, new emerging factors, and asthma and related allergic disorders. A statement of the World Allergy Organization. World Allergy Organ Jul 14 8(1): 25. doi: 10.1186/s40413-015-0073-0.

D‘Amato G., Liccardi G., Frenguelli G. 2007: Thunderstorm-asthma and pollen allergy. Allergy 62: 11–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01271.x.

19 - Haftenberger M., Laußmann D., Ellert U., Kalcklösch M., Langen U., Schlaud M., Schmitz R., Thamm M. 2013: Prävalenz von Sensibilisierungen gegen Inhalations- und Nahrungsmittelallergene – Ergebnisse der Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsbl, 56: 687–697. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1658-1.

20 - Deutschlandwetter im Frühjahr 2019: https://www.dwd.de/DE/presse/pressemitteilungen/DE/2019/20190529_deutschlandwetter_fruehjahr.html.

20 - Deutschlandwetter im Frühjahr 2020: https://www.dwd.de/DE/presse/pressemitteilungen/DE/2020/20200529_deutschlandwetter_fruehjahr2020.html.

21 - Bergmann K.-C., Buters J., Karatzas K., Tasioulis T., Werchan B., Werchan M., Pfaar O. 2020: The development of birch pollen seasons over 30 years in Munich, Germany – An EAACI Task Force report. Allergy. 2020 Dec; 75(12): 3024-3026. doi: 10.1111/all.14470.

22 - Rojo J., Oteros J., Picornell A., Maya-Manzano J.M., Damialis A., Zink K., Werchan M., Werchan B., Smith M., Menzel A., Timpf S., Traidl-Hoffmann C., Bergmann K.C., Schmidt-Weber C.B., Buters J. 2012: Effects of future climate change on birch abundance and their pollen load. Glob Chang Biol., 27(22): 5934-5949. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15824.